I wrote recently about how political pressure on FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn in 2020 may have helped the Texas firm Direct Biologics move their product ExoFlo forward inside the agency.

Today I analyze the ExoFlo Phase I clinical trial paper used in that push on Hahn to get the firm the IND for a Phase II trial. In my review as a cell biologist interested in bioethics and clinical trials, I found many questions and potential red flags in this paper.

I’ve divided today’s article into sections listed below and you can jump to specific topics by clicking on them.

Background | Sponsor | Role for Direct Biologics? | No financial disclosures | Puzzling funding section | FDA compliant? | Expired IRB? | Inconsistent trial dates | Results | Strengths & weaknesses | ISCT Concerns | First author saved by ExoFlo? | Looking ahead

ExoFlo paper background

In 2020 Direct Biologics was seeking an okay for a Phase II trial via an FDA IND. They got it cleared rather quickly after a Texas GOP Congressman, Michael McCaul, appeared to pressure Hahn.

The Phase I clinical trial paper on ExoFlo that seemed to have a pivotal role in this was published in the journal Stem Cells and Development.

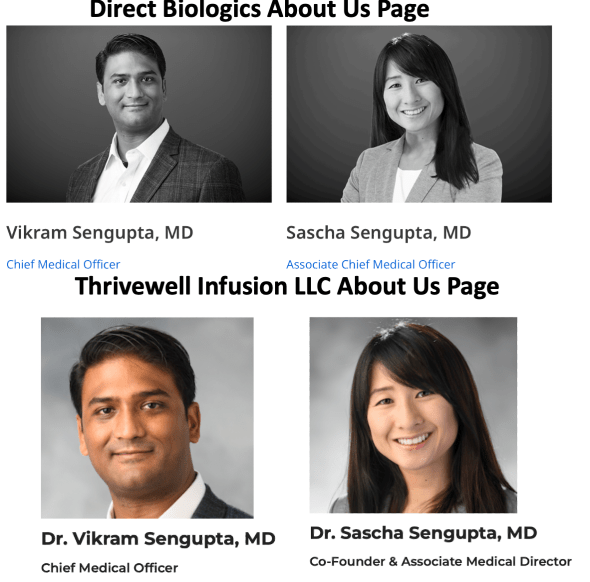

For reference, the authors of the ExoFlo paper were Vikram Sengupta, Sascha Sengupta, Angel Lazo, Peter Woods, Anna Nolan, and Nicholas Bremer. Note that the two Senguptas are now leaders at Direct Biologics.

How did I first get interested in this paper?

Rep. McCaul sent a PDF of the paper to Commissioner Hahn and in part based on the paper he pushed for quick FDA action to help Direct Biologics. McCaul threatened to go higher up the ladder, possibly to Trump.

For that reason, a major question follows: how solid was the science in this Phase I paper?

In it, the authors reported testing ExoFlo in COVID patients and were generally upbeat about their results. In my view this small, open-label, non-controlled study wasn’t designed to produce concrete conclusions, especially not about efficacy.

Still, such studies can provide initial insights into safety. A paper of this kind also could, in theory, be the basis for an IND application.

However, in my opinion this paper has so many issues that it leaves me wondering even more about the ExoFlo IND review process at the FDA.

Who is the sponsor of the ExoFlo study?

A good place to start in thinking about clinical trial papers like this one is to determine the trial sponsor. They’re in charge of the study and responsible for designing and running it properly. In this case with ExoFlo, I initially thought that Direct Biologics would be the sponsor. They manufacture the ExoFlo drug product that was tested.

However, the paper seems to indicate that the Senguptas’ firm, called Thrivewell Infusion, LLC was in charge of the study.

For instance, the paper says that Thrivewell Infusion acquired the ExoFlo product from Direct Biologics, which is mentioned only secondarily.

Any role for Direct Biologics?

The first two authors, the Drs. Sengupta, are leaders of Thrivewell so that’s straightforward, but they seem to have very similar roles also starting in mid-2020 at Direct Biologics. See the images above from the two firms’ websites.

On Vik Sengupta’s LinkedIn page it notes he became a leader at Direct Biologics in June 2020. That would be just weeks after the Phase I trial paper was published.

Could that explain why, as of May 2020 when the paper came out, he didn’t technically consider himself part of Direct Biologics?

How did they quickly become leaders at Direct Biologics right after the paper’s publication?

Why didn’t Direct Biologics sponsor this trial itself? Did it have a financial connection to the trial?

No financial disclosures

With that last question in mind, next I looked for financial disclosures in the paper. Under the Author Disclosures section of the paper, they state, “No competing financial interests exist.” That was surprising to me.

The Senguptas clearly are leaders of Thrivewell Infusion, LLC and were in 2020 when this paper was published.

It could make sense to have no competing financial interests if Direct Biologics had zero role and if Thrivewell were a non-profit entity, but I haven’t seen any indication that Thrivewell was or is a non-profit. If the study in question was successful, wouldn’t that help Thrivewell financially?

Exoflo Trial funding

Another thing one can look at when evaluating clinical trial papers is the funding. Trials are very expensive. I wondered how this study was funded. The Funding Information section of the paper is also puzzling:

“This study was supported by Drs. Vikram and Sascha Sengupta in collaboration with Christ Hospital. None of the authors were compensated for this study. Thrivewell Infusion, LLC provided acquired, commercially available product from Direct Biologics, LLC, Austin, TX, storage, medical supplies, transportation, legal resources, as well as supportive administrative and clinical personnel. No governmental funding of any kind was used to support this study.”

To me this section suggests that the two Drs. Sengupta personally paid for some major part of the costs of the study. Is that correct? To my knowledge, it would be extraordinary for clinical trial investigators to personally pay even part of trial costs.

It also seems that Christ Hospital chipped in and Thrivewell Infusion contributed too, but did Direct Biologics have no role in supporting the trial?

Another major question here is whether the study required some kind of payment by the participants, meaning the COVID patients or their families. It’s not clear.

Part of the reason I ask is that ExoFlo has already been marketed for other medical conditions and people have paid for the treatment that is not covered by insurance. As best as I can tell, this apparently was happening even without FDA approval. It appears that individual doctors and clinics are still offering ExoFlo for these other indications. Just Google “ExoFlo hair loss”, for instance.

FDA compliance?

Next, I wondered if the Phase I trial reported in the paper was conducted in an FDA-compliant manner. Here again, things are unclear.

The product, ExoFlo, in my view appears to be a drug. You need FDA clearance to do trials on a drug just as the firm later got INDs for both Phase II and Phase III ExoFlo studies.

I don’t see any indication about whether the team had an IND or some other clearance from the FDA for the Phase I study reported in the paper. Why would they have gotten INDs later for the Phase II and III trials and not for the Phase I trial?

If there wasn’t an IND for the Phase I study, maybe the team’s view of ExoFlo as to how FDA regs applied to it changed over time?

It’s possible and as things moved forward Direct Biologics became the sponsor, which could have led to different views of FDA regulations.

Still, as I noted in my previous post on ExoFlo, Direct Biologics did indicate in an internal document at one point that they felt some of their product was exempt from drug classification. But what’s key here is the FDA view at the time of the Phase I trial. The agency defined exosomes as drugs in a December 2019 notification to the public, which is prior to the Phase I trial.

What about an FDA okay for compassionate use that somehow could be folded into this Phase I trial? Compassionate use was mentioned in the paper along with an IRB:

“The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Christ Hospital’s institutional review board (approval number IRB 2020.01) under emergency compassionate use rules for immediate enrollment.”

What does the statement “emergency compassionate use rules for immediate enrollment?” mean? I haven’t seen this language used by sponsors of other trials. Did the FDA grant expanded access status? Or instead somehow this was decided by the Christ Hospital IRB? The language in the passage above suggests to me it was perhaps a local decision, but it’s not entirely clear.

Trial registration and IRB status?

Sometimes Clinicaltrials.gov listings can help clarify questions about trials. However, I couldn’t find the Phase I ExoFlo trial registered on Clinicaltrials.gov. That’s another potential red flag for me.

What about the IRB mentioned in the paper? It says the IRB was at Christ Hospital, which is in New Jersey.

While generally IRBs are required to be actively registered with the FDA to oversee a clinical study, this IRB seems to have expired back in 2019, before the study was run as reported in the paper. See the screenshot above from the federal IRB database.

Did the study have some other federally-registered and non-expired, valid IRB with a name different from that listed in the paper?

Inconsistent trial dates?

Let’s look more into the paper itself.

I find the dates the paper reports in various places in the text for patient enrollment to be puzzling. Related to the dates, what patient data were (or were not) included in the final analysis? Below I’ve highlighted different dates that to my mind seem somewhat inconsistent.

The first sentence of the Methods section seems straightforward:

Patients were enrolled…from April 8 to April 28, 2020

However, the last sentence of the same Methods section says:

The analysis population included all patients who received their first dose of ExoFlo before April 14, 2020, and for whom clinical data for at least one subsequent day were available.

What about the patients enrolled between April 14 and April 28? Were they excluded for some concrete reason?

Then the second sentence of the Results section in my view makes things less clear:

Seventeen males (age range: 45–84 years) and 10 females (age range: 29–75 years) were enrolled from April 6 to April 13, 2020.

I thought enrollment started on April 8 and went through the 28th.

How do these three separate mentions of date ranges jive together?

Results and Discussion

The abstract reports these outcomes: “A survival rate of 83% was observed. In total, 17 of 24 (71%) patients recovered, 3 of 24 (13%) patients remained critically ill though stable, and 4 of 24 (16%) patients expired for reasons unrelated to the treatment.”

The paper also notes, “No infusion reaction or adverse events were observed in any cohort within the first 72h. No adverse events were attributable to the administration of ExoFlo. Adverse events in Table 2 included worsening hypoxic respiratory failure re- quiring intubation (n = 4), pulmonary embolism (n = 1), acute renal failure (n = 3), and expiration (n = 4)—all events occurring >72h after treatment in seven patients, which were evaluated by the DSMB to be reasonably attributable to COVID-19 progression or to a clear temporally correlated provoking stimulus.”

It’s notable that 16% of patients (N=4) in the trial died. The DSMB reportedly found no reason to think that any adverse events could be related to ExoFlo. How solid is that conclusion?

In my previous post on the political pressure in this case I noted that an internal FDA text suggested the agency possibly had concerns about potential “ongoing deficiencies” with the IND application.

Overall, it’d be great to know how FDA analysts viewed this Phase I trial paper. Of course, that’s not likely to come out.

Strengths and weaknesses

The paper’s Discussion mentions strengths and limitations. It argues for these specific strengths of the study (emphasis mine):

Overall, the strengths of this study include minimal selection bias in addition to absence of financial sponsorship as the study was prepared, designed, and implemented by independent clinicians.

Again, how could they be independent physicians since both Drs. Sengupta were leaders at Thrivewell? Do they mean independent from Direct Biologics at the time?

How was this trial possible without financial sponsorship?

ISCT concerns

Note that members of ISCT, a global society of gene and cell therapy researchers, wrote a concerned letter to the editor in the same journal in response to this trial paper. The ExoFlo authors then replied to that.

The ExoFlo trial team response publication included new authors as compared to the original trial paper. These new authors, Kevin C. HicokTimothy Moseley, declared competing financial interests related to their leadership roles at Direct Biologics, but the other authors here again declared none. The author list on this July 2020 response pub includes the Senguptas. As noted earlier, Vikram Sengupta by this time seemed to be a leader at Direct Biologics per his LinkedIn page. And they both still had their Thrivewell business. How can there be no financial disclosures listed for them on this second paper? An oversight?

In terms of the ISCT questions and concerns, they asked about cGMP standards, characteristics of the ExoFlo product and dose, how the DSMB could rule out certain events, and more.

First author quoted: ‘ExoFlo saved my life’

There’s also possibly another element to this story that raises further potential issues in my view.

Dr. Vikram Sengupta reportedly became ill with COVID himself in 2020:

“Dr. Sengupta soon fell victim to COVID-19 himself and noted that he “became seriously ill fast.” Dr. Sengupta said that he woke up in the middle of the night struggling to breathe and checked his O2sat, realizing he was going into respiratory failure. He called his wife who left her shift at the hospital and promptly administered ExoFlo at their home.

“Within 24 hours my supplemental oxygenation requirement, fever, and respiratory symptoms significantly improved,” he continued. “And within five days of that single dose, I was almost fully recovered from the acute infection. I firmly believe that ExoFlo saved my life.”

Per this account, somehow Sascha Sengupta was able to obtain the investigational drug ExoFlo. Then she apparently administered it to her husband Vikram at home? How did she obtain ExoFlo and is it permissible for her to have used an unapproved drug on her husband and at home?

Also, the report says that Vikram believes that ExoFlo saved his life.

In that context, depending on the timing here, is it then permissible for him to serve as a leader of a clinical trial of ExoFlo for COVID and write up a paper on it? Can one be impartial after that kind of personal experience?

Is the Kazmir website’s report accurate on all of this?

Looking ahead on Direct Biologics and ExoFlo

Overall, this ExoFlo paper and the trial it reports have many potentially serious issues in my view. I reached out twice to Vikram Sengupta for comment and with my questions. I may do an update or follow-up post if I get a reply.

I’m very curious to see the Phase III results. Also, so far I have not seen a paper on the Phase II ExoFlo data. I hope we see that paper so the field can analyze the data.

Maybe more information can help clear up some of the questions on the Phase I study, which is crucial.

I also reached out to the journal Stem Cells & Development and am hoping I can share some official comment from them on my concerns, which include the journal action dates on the manuscript listed on the last page.

Hi Paul

An introductory statement in your analysis caught my eyes: However, I couldn’t find the Phase I ExoFlo trial registered on Clinicaltrials.gov. That’s another potential red flag for me.

However, five trials are listed in this registry – https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=exoflo&cond=COVID-19&draw=2&rank=2#rowId1

@Uriel,

Yes, but it seems to me that none of these are the Phase I trial published in the paper that started this whole line of clinical research. The oldest listing I see is the Phase II trial.

Hi Paul,

What do you think of now that Direct Biologics is in Phase 3 for all cause ARDS with Phase 2 results published? Curious to see your thoughts now that a lot more information is available about the ARDS trial as well as some others for Crohn’s & UC.

l am on the road, using my phone, please excuse spelling errors.

Whats your point? You don’t like this trial? The FDA is the regulatory agency and the IRB is responsible for the trial as it progresses. It’s a long process. If evidence is deemed influenced, it will be duscarded and the discarded pieces will need to be duplicated at the study’s cost. Let it play it out and if corrections need to be made its up to the IRB initially. INDs are very complicated and much of the IND is propriatary. So of course, you can only see pieces of the study and make guestimations at best.

This “hit piece” written is all over the place. The actual point of the article ia hard to address. If we like a company, person, doctor or not, we should be supporting smaller companies, and physicians that don’t have the same pocket books as big pharma trying to push cellular science forward and not trying to tear them down for what looks to be a personal vendetta. Why not look at some of the side effects, and contraindications that have recently been overlooked or concealed intentionally by multibillion dollar drug companies?

@Vince,

Big or small, clinical trials need to follow the rules.

You need an active, registered IRB. If you’re studying a drug, you need to work with the FDA and have an IND before you do the trial. You shouldn’t charge people to be in the trial. You should be 100% transparent about the finances and potential COIs. You should register the trial on Clinicaltrials.gov. Data in the paper should be consistent such as dates of enrollment, which patients were used in the analysis, etc. If there are severe adverse events including deaths, these need serious evaluation by DSMBs, the FDA, etc.

It’s also possible for IRBs and the FDA to make mistakes. In my view the FDA has made some important mistakes with overseeing trials in the past with both big and small trials and drug decisions.

All of these things are worth discussing and hashing out. I have no personal interest in any companies working on exosomes so there’s no reason for me to do a “hit piece” or to have a vendetta.

This piece is just my analysis of this unusual situation. In the regenerative medicine space, I write about my views and have high expectations for trials in general. I also reached out to the company and authors politely with some questions multiple times but never heard back. They could have helped clarify some things I’m sure.

As I’ve acknowledged before, some unpublished data can be important parts of IND efforts too.

Thanks for the thorough review!

Wow! Thank you for sharing your concerns about this “study”